Modi flags concerns on Hindu safety as Yunus edges Bangladesh closer to China and Pakistan

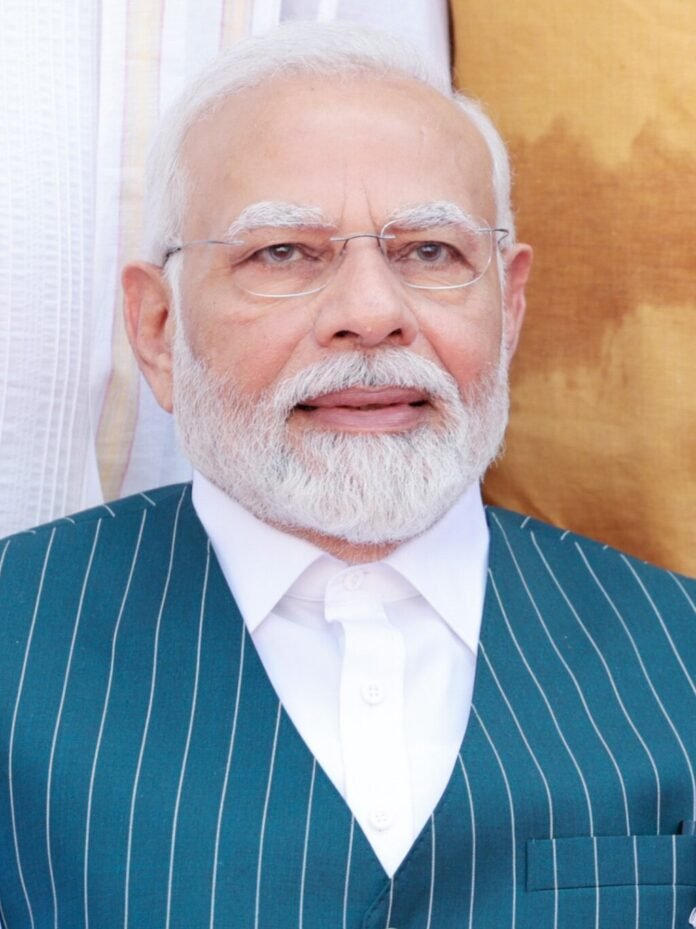

Prime Minister Narendra Modi met Bangladesh’s transitional leader Muhammad Yunus in Bangkok on Friday, signalling a tense recalibration in India-Bangladesh ties amid Dhaka’s growing warmth towards Beijing and Islamabad.

The meeting, which took place on the sidelines of the BIMSTEC Summit, lasted around 40 minutes and marked the first face-to-face exchange between Modi and Yunus since the latter replaced Sheikh Hasina as Bangladesh’s Chief Adviser in August 2024. The encounter came at a delicate moment, with regional alignments shifting and old alliances under stress.

Modi used the opportunity to raise India’s mounting concerns over the safety of Hindu minorities in Bangladesh, a longstanding point of friction. Following Hasina’s ousting by a student-led uprising, sectarian violence surged across Bangladesh, with minority Hindus often caught in the crossfire. The Indian government offered refuge to Hasina, who fled Dhaka by helicopter, and has since kept a wary eye on Yunus’s foreign policy choices.

Yunus, a Nobel laureate with no electoral mandate but considerable international support, has steered Bangladesh in a markedly different direction. Earlier this week, he met Chinese President Xi Jinping, asking Beijing to deepen its economic engagement with Dhaka. In a move that drew ire in New Delhi, Yunus hinted that India’s landlocked northeastern states could benefit from Chinese access to Bangladeshi ports — a comment perceived as provocative and strategically loaded.

Embed from Getty ImagesNew Delhi interprets this as a clear attempt by Beijing to exploit geographic vulnerabilities and widen its influence in South Asia. The Indian establishment, already wary of China’s presence in the Indian Ocean and its close defence ties with Pakistan, now sees Bangladesh drifting into that strategic orbit.

The Modi-Yunus meeting reflected these anxieties. While maintaining diplomatic decorum, Modi conveyed that “any rhetoric that vitiates the environment” must be avoided — a veiled but pointed reference to Yunus’s China remarks. Indian officials say Modi was firm but measured, pushing for a return to “mutual respect and regional stability.”

Compounding the concerns is Bangladesh’s surprising detente with Pakistan. Since the fall of Hasina, Dhaka has moved swiftly to restore ties with Islamabad, frozen for over a decade over the legacy of the 1971 Liberation War. Yunus’s administration has reportedly re-established diplomatic exchanges, fuelling fears in Delhi of a new China-Pakistan-Bangladesh triangle emerging just across its eastern border.

India’s response is expected to go beyond diplomacy. There is speculation that New Delhi may increase economic and strategic engagement with Bangladesh’s neighbours, including Myanmar and Sri Lanka, to hedge against Dhaka’s tilt. Additionally, it may ramp up pressure through international channels over human rights violations, particularly the persecution of minorities in Bangladesh.

Despite the growing tension, both sides emphasised their “historic ties” in post-meeting statements. Indian officials described the talk as “frank and forward-looking”, while Bangladeshi sources downplayed the strategic divergence, insisting Yunus remains committed to “balanced foreign policy.”

Yet the writing on the wall is clear. Sheikh Hasina’s fall has reshuffled the regional chessboard, and Modi’s meeting with Yunus was less about camaraderie and more about caution. As Dhaka cosies up to India’s biggest rivals, New Delhi finds itself confronting an uncomfortable question — can it still count on Bangladesh as a friend in the neighbourhood?