In a groundbreaking experiment, South Korea’s Kstar sustains plasma at 100 million degrees for 48 seconds, marking a significant advance in nuclear fusion research

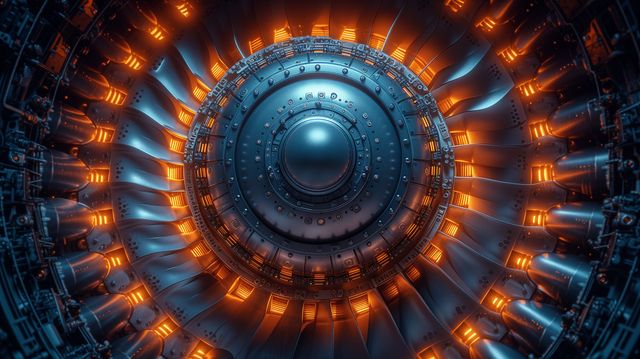

In an unparalleled scientific achievement, South Korea’s Korea Superconducting Tokamak Advanced Research (KSTAR) device, colloquially known as the “artificial sun,” has set a new world record by sustaining temperatures of 100 million degrees Celsius for 48 seconds. This temperature, seven times hotter than the core of the sun, represents a monumental stride in the field of nuclear fusion, a technology that mimics the processes powering stars, offering a potentially limitless and clean energy source for the future.

Nuclear fusion, which combines two atoms to release vast amounts of energy without emitting carbon, has long been heralded as the ultimate solution to the world’s energy needs and environmental challenges. However, replicating this stellar process on Earth has proven to be a formidable task, fraught with technical and scientific hurdles.

Embed from Getty ImagesThe recent success at the Korean Institute of Fusion Energy (KFE), home to KSTAR, is a pivotal advancement towards making fusion energy a reality. According to Si-Woo Yoon, director of the KSTAR Research Center, achieving and maintaining high-temperature and high-density plasma states, where fusion reactions can occur continuously, is crucial for the development of future nuclear fusion reactors. This achievement addresses the intrinsic instability of high-temperature plasma, underscoring the significance of the new duration record.

KSTAR’s progress in extending the operational time of plasma at such extreme temperatures, from a previous best of 30 seconds in 2021 to 48 seconds, was facilitated by modifications to the experimental setup. One such adjustment involved the use of tungsten in place of carbon in the device’s diverters, components crucial for extracting heat and byproducts from the fusion reaction.

The goal for KSTAR is to further push the boundaries by sustaining 100 million degrees plasma for 300 seconds by 2026, a milestone Si-Woo Yoon describes as “a critical point” for scaling up fusion energy operations. This endeavour is not only pivotal for South Korea’s fusion program but also contributes valuable insights to the global fusion research community, particularly benefiting the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) in France, which aims to demonstrate the practical feasibility of fusion power.

Despite these remarkable achievements, the commercialization of nuclear fusion remains on the horizon, with scientists worldwide continuing to tackle the formidable engineering and scientific challenges inherent in this technology. While not an immediate solution to the current climate crisis, the ongoing advancements in fusion energy hold promise for its integration into the future green energy mix, potentially revolutionizing how the world generates power by the latter half of this century.